An Analytical Approach to Rudiments: Part One, Types of Strokes and Stickings

As my students hear on a regular basis, the study of rudiments is crucial for developing a solid technical foundation as a percussionist. I think of rudiments as a percussionists' basics and essentials, but not because they are easy or meant only for beginners. The 40 Percussive Arts Society International Drum Rudiments encompass a huge variety of combinations of different types of strokes and stickings that, when mastered at a variety of tempi and dynamics, leave the player well-prepared to tackle most technical challenges in music.

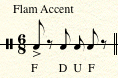

Let me explain more of what I mean by types of strokes and stickings.

I conceptualize all snare drumming (excluding only multiple-bounce and double-stroke rolls) to be made up of four basic types of strokes:

- Full stroke: the stick starts high, rebounds, and ends in the starting position. (Full stroke can occur at any dynamic, with starting stick height to be adjusted to create desired dynamic.)

- Down stroke: the stick starts high, the rebound is controlled, and the stick ends low (very close to the drum head).

- Up stroke: the stick starts low, the rebound is assisted by the player's wrist and arm, and the stick ends high.

- Tap: the stick starts low, and ends low, in starting position.

The type of stroke for any note depends on two factors: the volume of the note in context of the rudiment or musical passage, and the height of the note that follows. In other words, every stroke consists of two parts: the "pre-stroke" prepares to strike the drum and create the sound of the note on the page, and the "post-stroke" serves to set up the proper stick height for the following note.

The term "stickings" simply refers to playing each note with either the Right or Left hand. Many players, especially beginners, have a strong predisposed preference for one hand, and the ideal is to become equally competent and comfortable with both hands, and with any combination of stickings that the music may demand. To tackle this skill, I recommend starting with the four Diddle Rudiments in group II. of the PAS International Drum Rudiments and the Single Beat Combinations that begin on page 5 of G. L. Stone's Stick Control.

As an educator, one of my primary goals is always to equip students with the basic musical and technical skills they'll need for a variety of musical situations and challenges that may exist in their futures. For percussion students, this means studying and mastering the basics, including types of strokes, stickings, and rudiments.

For more on the four basic types of strokes and their application to specific rudiments, keep reading to see my next post, Part Two: Application of the Strokes.